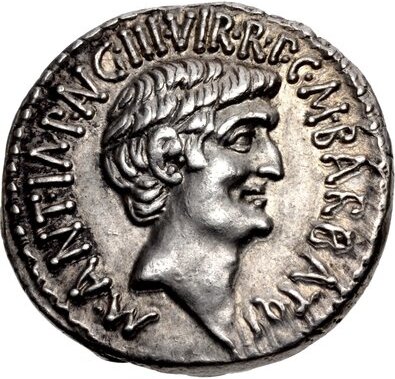

Mark Antony: The Roman Leader Who Fell Short of Power

A brilliant soldier and Julius Caesar’s most loyal ally for years, Mark Antony appeared poised to become Rome’s new leader after his mentor’s assassination. However, his missteps in governance, disregard for the rising Augustus, indulgence in luxury, and his affair with Cleopatra ultimately led to his downfall.

Perhaps, as Mark Antony lay mortally wounded by his own sword, his thoughts drifted back to the days of glory and triumph, when the fate of Rome rested in his grasp. He might have recalled the distant memory of his mother, Giulia, or his father, who died when Antony was still a child. Or maybe his mind wandered to his wild youth, spent alongside his closest companion, Gaius Scribonius Curio. Together, they shared countless nights of drunken revelry, wandered through infamous haunts, and dodged relentless creditors seeking repayment of their enormous debts. All of this unfolded in a turbulent Rome, gripped by social unrest and rife with political conflict. Antony, too, would soon be drawn into these struggles, standing shoulder to shoulder with the man who would become his mentor: Gaius Julius Caesar, the conqueror of Gaul. But first, Antony had to build a name for himself—a reputation that would allow him to step onto Rome’s volatile political stage.

Wasted youth

Mark Antony was born in Rome on January 14, 83 BC, into an influential yet plebeian family. His grandfather, a prominent orator who served as consul and censor, was a key figure in Sulla’s party but was executed by Marius during the power struggles between the optimates and populares in the early 1st century BC. Antony grew up without his father and led a reckless youth, forming a close friendship with Curio, who, according to the historian Plutarch, “dragged him into a life of debauchery, involving prostitutes and excessive, unbearable expenses,” leaving Antony deeply in debt.

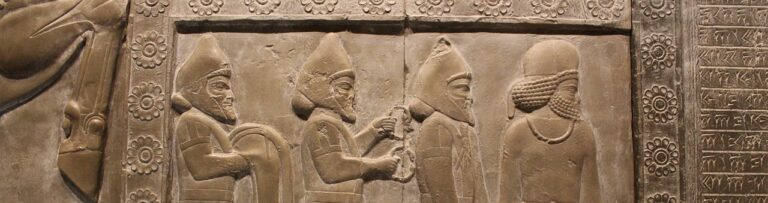

Antony’s introduction to public life came through Publius Clodius Pulcher, a notorious figure involved in subversion and corruption. Realizing that the scandals surrounding him were damaging his reputation, Antony chose to leave Rome. In 56 BC, he traveled to Greece, where he studied oratory and attended lectures. A year later, he joined the army of Proconsul Gabinius as a cavalry commander, receiving his first taste of battle during the Syrian campaign. Antony quickly distinguished himself for his bravery, boldness, and strategic insight. Earning Gabinius’ trust, he led his legions into Egypt to restore Ptolemy XIII Auletes to the throne.

Caesar’s right-hand man

Mark Antony’s early military successes paved the way for his return to Rome, where he reunited with his friend Curio. Once a supporter of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus—renowned for his military achievements—Curio had now switched sides, aligning with the populares faction led by Julius Caesar. Following his old companion’s advice, Antony journeyed to Gaul, where he took part in several military campaigns under Caesar’s command. Impressed by Antony’s talents, Caesar sent him back to Rome, where he quickly ascended the ranks of the cursus honorum, taking on various judicial roles.

From this point forward, Antony became one of Caesar’s most trusted allies and an active political agent. He played a key role in opposing the plans of Pompey and the senatorial nobility, representing Caesar’s interests as tensions in the Republic deepened.

On December 10, 50 BC, Mark Antony and Quintus Casius appeared before the Senate, advocating for Caesar’s positions and launching a major campaign to rally public support for him. At the start of the following year, a heated debate arose in the Senate regarding the simultaneous disbanding of Caesar’s and Pompey’s armies. Supporters of Caesar backed the dissolution, while Pompey’s allies vehemently opposed it. The discussion culminated in the expulsion of the tribunes of the plebs from the chamber and the granting of sweeping powers to Pompey to defend the Republic. This power shift escalated tensions, leading to a full-blown conflict between the two triumvirs and the onset of civil war.

In January 49 BC, Caesar crossed the Rubicon with Mark Antony by his side. Within six months, he would gain control over Italy and Rome, assigning key positions to his most loyal supporters while immediately heading to the Iberian Peninsula to confront Pompey’s armies. Antony remained in command of the troops in Rome, where he engaged in various abuses regarding economic management and justice administration during Caesar’s absence.

However, an opportunity soon arose for him to rush to support his mentor, who was besieged in Dyrrachium (modern-day Albania). Despite challenging weather and rough seas, Antony managed to embark eight hundred horses and twenty thousand men, arriving just in time to aid Caesar. In 48 BC, he stood alongside Caesar at the Battle of Pharsalus, where they achieved a decisive victory against Pompey. Caesar’s strategic brilliance, combined with Antony’s courageous command of the left flank, led to the annihilation of Pompey’s forces. Pompey fled to Egypt, where he met his end at the hands of the Ptolemies.

Upon returning to Rome, Mark Antony was appointed by Caesar as his lieutenant and effectively became the master of the city’s affairs. However, his military renown was overshadowed by his poor governance, which bordered on despotism. Antony’s behavior contradicted the image of moderation that Caesar aimed to project to the populace. His private life became a scandal in Rome; he surrounded himself with entertainers and prostitutes, hosted extravagant banquets that often ended in drunken debauchery, and his entourage frequently caused disturbances in the cities he visited along the peninsula.

As punishment for his excesses, Caesar stripped Mark Antony of the consulate upon returning from his eastern campaigns. In response, Antony moderated his behavior; he married Fulvia, the widow of Curio, and purchased Pompey’s lavish house in Rome. After the civil war, Antony, now serving as Caesar’s colleague in the consulate, crowned the dictator with a royal diadem during the Lupercalia celebrations—an act Caesar refused three times. This theatrical gesture failed to sway the opposition, who feared that if Caesar succeeded in his upcoming campaign against the Parthians, he would declare himself an absolute monarch. There seemed to be no other option: the dictator had to be eliminated.

The murder of Caesar

Sixty prominent figures, many of whom were former collaborators and friends of the dictator, gathered in Pompey’s Curia, led by Gaius Cassius Longinus and Marcus Junius Brutus, his brother-in-law. There, they assassinated Caesar beneath the statue of his historic enemy while Antony, held back at the entrance, listened helplessly to his mentor’s screams. In the aftermath, Antony resolved to seize power, as was fitting for his judicial role. He convened the Senate, which granted amnesty to the conspirators, abolished the dictatorship, and restored the Republic.

In the months that followed Caesar’s death, Antony established himself as the master of Rome. However, when he attempted to alter the distribution of provinces to his advantage, he clashed with Decimus Brutus, the governor of Cisalpine Gaul.

It was during this tumultuous time that the young Gaius Octavius Turinus emerged on the Roman political scene. The son of Caesar’s niece, who had named him her heir, he returned from Apollonia to claim his rightful position. Overlooked by Antony, who dismissed him as young and inexperienced, Octavius adopted the name Gaius Julius Caesar Octavian. Through his own efforts, he amassed a fortune and garnered popular support. Thus, while Antony headed to Modena to confront Decimus Brutus, Caesar’s heir began forging alliances with influential senators, particularly Cicero, who seized the opportunity to criticize Antony’s reckless behavior in his Philippics.

The Senate declared Antony a public enemy. Defeated, he fled to Gaul, while Octavian secured the consulship and began to prosecute the assassins of his adoptive father. To strengthen his position, he convened a meeting with Antony and Lepidus in Bologna, where the three formed the Second Triumvirate. Their objectives were to punish Caesar’s assassins, redistribute control of the provinces, and eliminate Octavian’s political rivals. After defeating Brutus and Cassius, Octavian received the province of Hispania, Lepidus took Africa, and Antony was assigned the East.

From Ephesus, Antony traveled through Asia Minor to restore order in his territories, and upon reaching Tarsus, he summoned Cleopatra, the queen of Egypt. Their meeting was nothing short of love at first sight; Antony followed the queen to Alexandria, where he became consumed by luxury and festivities, neglecting his duties as a soldier and sovereign.