Roman Britain: The Empire’s Influence on the Isles

For four centuries, thousands of legionaries defended the empire’s most remote frontier, until, after the great barbarian invasions, Britain was left abandoned.

Around 410 AD, the citizens of Britain appealed to the Roman Emperor Flavius Honorius for assistance against the barbarian invasions that had been ravaging their lands since the mid-4th century. However, the emperor urged them to defend themselves, effectively acknowledging that he could no longer send Roman troops to this distant province and, therefore, could no longer maintain his authority over Britain. This marked the official recognition of the end of Roman rule in Britain, which had begun four centuries earlier. After Julius Caesar’s initial attempts at conquest in 55 and 54 BC—when he sacked the lands of the Trinovantes north of the Thames Estuary—it was Emperor Claudius, in 43 AD, who finally succeeded in repeatedly defeating the powerful British tribe, the Catuvellauni.

The conquest of Britain was anything but straightforward. In the four years following Claudius’ expedition, led by Aulus Plautius, former legate of Dalmatia and Pannonia, the Roman army only managed to secure the central part of the island, failing to subdue the fiercely independent tribes inhabiting the other regions. Even with three legions stationed in the Roman colonies of Lindum (Lincoln), Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter), and Glevum (Gloucester), the British tribes resisted, resolutely opposing the invaders.

In the years after the initial conquest, several revolts erupted, including the bloody insurrection led by Boudicca, queen of the Iceni and a Druid priestess, during the administration of Gaius Suetonius Paulinus. Around 120 AD, another uprising, of which little is known, was instigated by the inhabitants of Eburacum (York) and resulted in the destruction of the Ninth Roman Legion.

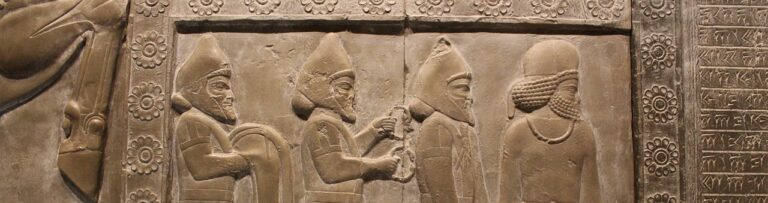

Between 78 and 85 AD, General Julius Agricola expanded Roman control into northern Britain, securing territory inhabited by the Brigantes. Following a subsequent rebellion in 122 AD, Emperor Hadrian ordered the construction of the wall that now bears his name. Stretching from the mouth of the River Tyne to the Solway Firth, this fortification marked the boundary between Roman-controlled England and Scotland. Later, Emperor Antoninus Pius launched a campaign against the northern tribes and erected another wall further north, between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde. However, this new defense failed to prevent further invasions from the northern peoples, as assaults continued even after the walls were completed.

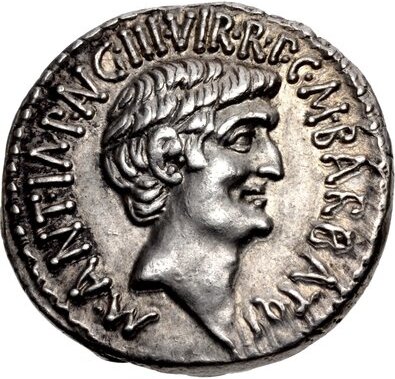

The crisis of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century had significant repercussions for Britain, leaving the island more vulnerable to invasions, raids, and uprisings by native populations. During this turbulent period, two usurpers seized power in Britain. The first was Carausius, a Roman soldier from Gallia Belgica, who had been tasked by Emperor Maximian with combating Frankish and Saxon pirates. Accused of embezzlement, Carausius fled to Britain, where he proclaimed himself emperor. However, in 293 AD, he was assassinated by one of his own officers, Allectus, who became the second usurper to claim imperial power over the island.

In 296 AD, Constantius I, known as Chlorus, one of the two Caesars appointed by Emperor Diocletian during the era of the Tetrarchy, launched a major expedition to reclaim Britain. The local population welcomed him favorably, and during his stay, Constantius enacted an administrative reform, dividing Britain into four provinces: Britannia I, Britannia II, Maxima Caesariensis, and Flavia Caesariensis.

Saxon Invasions on the Coast

The threat to Britain in this period came not only from land but also from the sea. Repeated raids by the Scots from Ireland and the Picts from Scotland were compounded by attacks from Frankish and Saxon pirates. This mixed group of Germanic and Frisian populations targeted the southeastern coastline, adding to the turmoil with their relentless incursions.

Maritime Defense and Barbarian Threats in the Late Empire

In response to the ongoing Saxon threat during the late empire, Britain reorganized its maritime defense. A comes litoris Saxonici per Britannias was appointed to lead the flotilla known as Sambrica, tasked with protecting both the British and Gallic coasts. To bolster naval defenses, new forts were constructed along the coastline, with archaeological evidence indicating that these fortifications were built or repaired until the early 5th century.

The 4th century saw relentless attacks from barbarian groups. The most significant threat was referred to as the barbaric conspiratio, detailed by the Latin historian Ammianus Marcellinus in Rerum gestarum libri. This conflict involved a long campaign by land and sea, in which a paramilitary group called the Arcani forged an alliance with various barbarian tribes. The Romans permitted these tribes to penetrate Pict territory across Hadrian’s Wall, while the Scots launched attacks on western Britain and the Franks and Saxons invaded northern Gaul around 367. In just one year, the conspirators sacked numerous cities on the island, jeopardizing imperial authority in Britain. In response, Emperor Valentinian I dispatched Theodosius the Elder, father of the future Emperor Theodosius I, to quell the uprisings. Theodosius successfully restored order, aided by the reconstruction of Hadrian’s Wall.

The invasions in the northern part of the island appeared largely disconnected from the conspiracy that impacted southern Britain. However, Theodosius could not prevent the Scots from establishing a permanent presence in the western region of the island. Around 367, a new province across the Channel was formed, named Valentia in honor of the emperor, although scholars have yet to clearly define its borders.

Among the so-called clientes of the empire, Theodosius likely brought Magnus Maximus—a Spanish general who served under Emperor Valentinian I and his son Gratian—to Britain. After Theodosius was executed in 376, Maximus returned to Britain at the behest of Emperor Gratian to combat the barbarian threats. In 383, as a new wave of invasions by the Scots, Picts, and Saxons emerged, Maximus proved his prowess in battle by successfully repelling the invaders. That same year, in recognition of his military achievements, he was acclaimed Augustus by his soldiers.

Conspiracy in Britain

In Gaul, the usurper Magnus Maximus fought against Emperor Gratian, ultimately killing him in battle and gaining recognition of his imperial title from Theodosius I, who became Augustus of the East in 379. However, Maximus only gained control over Britain, Gaul, and Spain, while the rest of the Western Empire remained under the authority of Valentinian II, who was elected emperor in 375 and supported by Theodosius. Encouraged by his military successes, Maximus named his son Flavius Victor as Caesar in 384 and placed him in charge of Gaul while he campaigned in Italy against Valentinian II. In response, Theodosius I sent General Arbogastes to defend the emperor, and after Maximus’s death, Arbogastes had Victor killed in 388.

The events surrounding Magnus Maximus had significant repercussions for Roman Britain. Gildas the Wise, a 6th-century monk and author of the earliest chronicle about the Britons titled De excidio et conquestu Britanniae (On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain), noted that the province lost all its soldiers and armies with the departure of Maximus. Between the 5th and 8th centuries, Britons fleeing from the Saxon siege of the island migrated to Armorica, present-day Brittany in northern France. According to Gildas, this left Britain vulnerable to attacks from various peoples. Notably, the memory of Maximus endured among the British, as seen in the Mabinogion, an anthology of ancient Welsh tales. One of its characters recalls Magnus Maximus in a story featuring Macsen Wledig, who is introduced as the emperor of Rome.

By the early 5th century, the troubled state of the Western Empire, besieged by Germanic tribes along the Danube frontier, had consequences for Britain once again. In 402, Stilicho, a Vandal politician and general entrusted by Theodosius with the care of his sons, Arcadius and Honorius, managed to halt the Gothic invasions in Italy. These Goths were serving the Eastern Emperor Alaric, with whom Stilicho had previously fallen out of favor due to accusations of collusion with the barbarians. In Gaul, Honorius’s general initially succeeded in fending off the repeated threats from the Vandals, Alans, and other nomadic tribes. However, he eventually abandoned the province, which then allied with the invaders. Similarly, Britain was left to fend for itself without Rome’s guidance. In 407, a soldier stationed in Britain, known as Constantine III, marched onto the continent and was elected emperor in Gaul with the support of his troops. After securing several victories against the Vandals, he was initially recognized as emperor by Honorius but was later arrested and executed by Constantius, who would become the future emperor of the West.

The End of Roman Britain

These events signaled the final decline of imperial authority in the province across the Channel. During this tumultuous period, the Britons, facing renewed attacks from various barbarian groups, began to organize their defenses. Around 409, they expelled the remaining Roman officials from the island, a year that also saw the Bretons of Armorica removing the last imperial representatives from the continent.

For several decades, the Britons fought valiantly to protect their borders, often seeking refuge behind the walls of their cities against invading forces. By the mid-5th century, Vortigern, a semi-legendary king of southeastern Britain, attempted to leverage the Saxon invasions from the continent to counter the incursions of the Picts and Scots from the north. However, in 446, the Britons appealed to Aetius, a minister and general under the Roman Emperor Valentinian III, for assistance in their struggle against the Saxons.

Between the late 5th and early 6th centuries, many Britons fled to Armorica, which later became known as Brittany. Under the pressure of Germanic invasions, including those by the Saxons, Angles, and Jutes, who settled in increasing numbers in the eastern part of the island, the era of Anglo-Saxon rule began.