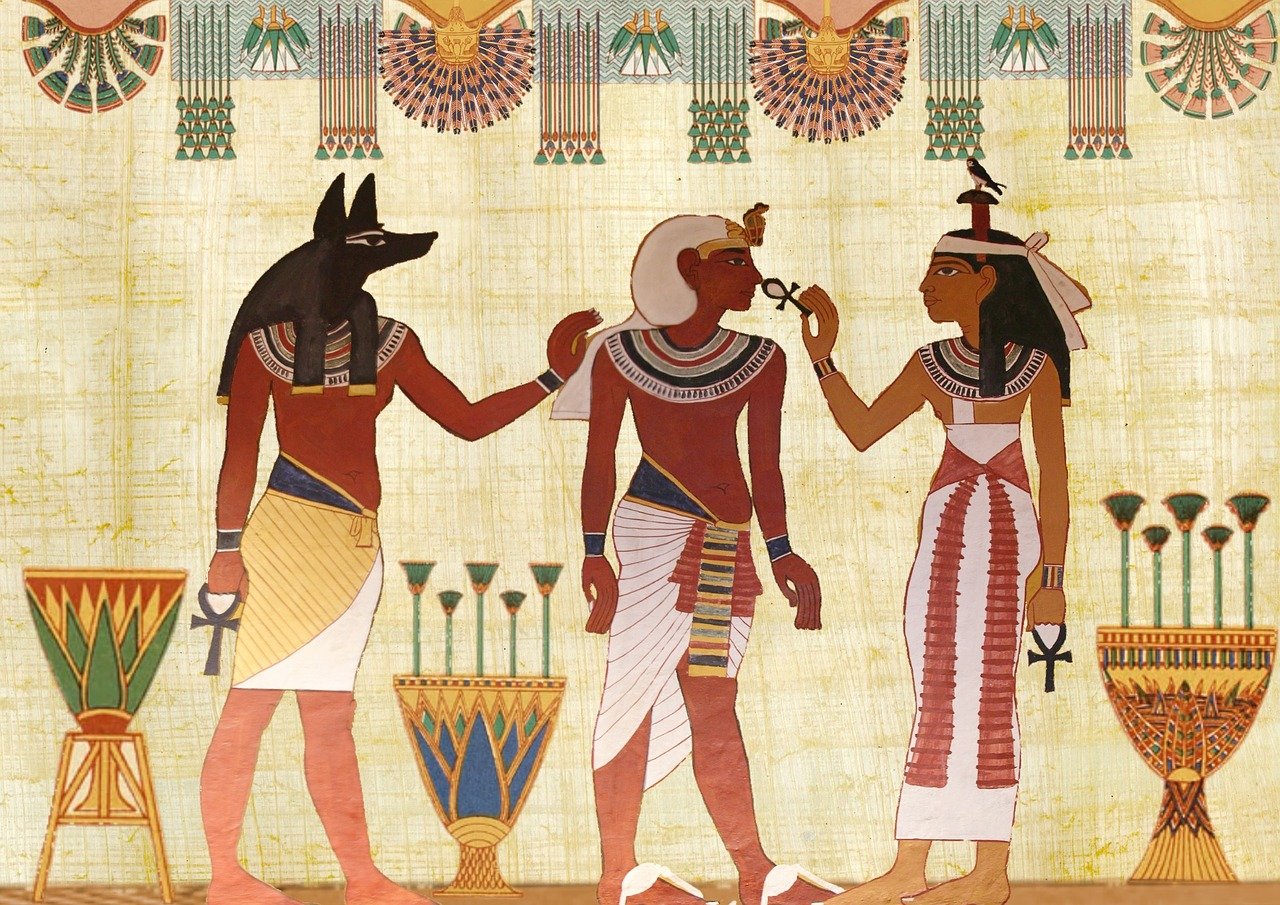

The life of an Egyptian nobleman favored by the pharaoh.

In the land of the Nile, those fortunate enough to attend the palace school embarked on a career in state service, with the potential to rise to the position of vizier, or prime minister. A lavish tomb marked their success in life.

We often envision Egyptian society as static, with children inheriting their fathers’ trades and existing in isolated social groups under the watchful gaze of an inaccessible pharaoh. However, this perception is misleading. In ancient Egypt, there was a degree of social mobility, essential for any community to prevent stagnation and decline. While farmers, artisans, small traders, modest civil servants, and servants faced limited opportunities, some individuals who received formal education and exhibited talent could aspire to professional and social advancement.

These fortunate few could rise to the privileged elite of Egyptian nobility and, if luck was on their side, attain the highest position beneath the pharaoh: vizier. Let’s explore the life of a “winner” in ancient Egypt, from birth to death. We might start by imagining that our protagonist’s parents married for love, as was often the case, as indicated by some known prenuptial contracts. In Egypt, marriage typically lacked formal ceremonies; couples simply moved in together, and their union was consecrated by this mutual decision, without the need for state or priestly recognition. Being young and healthy, pregnancies soon followed, spaced relatively apart, as women used contraceptives of varying effectiveness to manage family size.

Investing in education

The death of mothers or newborns during childbirth was unfortunately common, so women typically did not give birth alone or without assistance. When the time came, the woman would crouch on stone slabs adorned with magical symbols, supported by another strong woman behind her. The safety of both mother and child was ensured by a decorated hippopotamus tusk, an amulet dedicated to Tueret, the deity who protected pregnancy.

If our protagonist’s father was a low-ranking scribe, he likely encountered the world of written language and the magic of hieratic script from an early age. It was possible that another scribe took him under his wing for instruction. However, public schools as we know them today did not exist; the only institution available for aspiring nobles was the palace school. Thanks to his father’s connections, our protagonist may have entered this school around the age of ten, studying alongside the children of other officials, foreign princes held as hostages, and the pharaoh’s own children. One of these peers would eventually become a ruler, allowing our protagonist to form a circle of loyal allies who could support him once he ascended to power.

Egyptian educators believed that children learned better through discipline, often resorting to physical punishment to keep them attentive. After four years of training, a student would have acquired the basic skills needed to work as a low-level scribe: reading, writing, familiarity with fundamental characters, basic arithmetic, and practical problem-solving for everyday tasks like counting bags and calculating areas. Those who showed promise could continue their studies to become higher-ranking officials. Over twelve years, they would take on increasing responsibilities, enhancing their skills and knowledge.

Assuming our protagonist was fortunate enough to find a woman who returned his affections, they would marry and start their own family. Typically, married children lived with their parents in the Egyptian family structure, but given the small size of homes (around fifty to sixty square meters) and that he was not the firstborn, it was not uncommon for a son beginning his career to establish a separate household.

Ancient Egyptian homes were modest, consisting of a guest room, a main room, a bedroom, a pantry, and a kitchen, with any available terrace space serving as a communal area. As one’s fortunes improved, the size of the home could increase, or a new one might be constructed. The ideal residence was a spacious mansion with courtyards, storage areas, silos, a garden, a pond, a pergola, and numerous rooms arranged over two floors.

A Flourishing Career

To enjoy these luxuries, it was essential to complete assigned tasks to the satisfaction of superiors and hope that one’s good work reached the pharaoh’s ears through the vizier. A potential starting point on the path to higher administration could have been serving as an assistant to a land surveyor. Once the Nile flooded and receded from the fields, his role would involve accompanying the surveyor, carrying the land registry papyrus and reading it aloud while two subordinates measured the field boundaries, ensuring they remained unchanged by water or encroaching neighbors. Precision was vital, as the size of the fields directly affected the taxes owed by farmers.

Another significant role was participating in expeditions into the desert to search for minerals and special stones like basalt, graywacke, or red granite. This was a demanding and hazardous job, with over ten percent of participants at risk of dying during such missions. However, working as a military scribe and eventually leading expeditions would equip our protagonist with the skills to manage difficult men and challenging situations. A new promotion from superiors could also elevate him to the role of messenger, tasked with delivering communications from the king to foreign lands, military leaders, or other sovereigns.

By diligently performing his duties, our character emerged as a prominent figure in the court. When his former schoolmate ascended to the throne, he rewarded our protagonist’s dedication by granting him the esteemed title of vizier, the prime minister, thereby elevating him to noble status. This role brought immense power but also significant responsibility, requiring him to execute the pharaoh’s orders and report daily on the nation’s affairs—a responsibility highlighted during the investiture ceremony: “Here is the office of vizier: remain vigilant about all it entails, for you are the pillar of the country. The role of vizier is not enjoyable; it is as bitter as bile.” Indeed, the duties of judgment, ceremony, and taxation all fell to the vizier, demanding his attention.

Yet, for our protagonist, life was not solely about hardship. His home transformed into an important mansion, attracting a growing political clientele. Meanwhile, he and his family enjoyed hearty meals featuring ample meat—a luxury few could afford, as most Egyptians subsisted mainly on bread and beer, which resembled porridge and was nearly devoid of alcohol.

The final reward

After thirty years in power, the vizier had grown old; at sixty, he had lived nearly twice as long as the average Egyptian. His tomb had long been completed and awaited his mummy, ready for the moment when he would reunite with his ka, or life spirit, in the west. While the decoration of the hypogeum was typically a tribute from the monarch, it was the vizier’s responsibility to assemble the funerary objects that would accompany him into the afterlife and to establish a legacy that ensured proper offerings would be made for him and his wife, providing them with abundant sustenance in the realm of Osiris.

Usually, it fell to the children to serve as caretakers for their parents’ ka, but if they were preoccupied with their own careers, this only occurred on designated days. Thus, it was prudent for the vizier to designate which of his assets would be allocated for these offerings and to draft a contract with a trusted individual who would manage them daily.

Following his death, as per his wishes, the vizier’s body was embalmed, and his mummy was transported to its eternal resting place on the western bank of the Nile, accompanied by family and friends. There, after the opening of the mouth ceremony—ensuring his immortality—he was laid to rest, ready to enjoy his well-deserved eternal life.